Numbers don’t lie. But sometimes we lie to ourselves about what numbers represent.

Last week, I wrote a post about new research from ExactTarget that studied Americans’ digital channel preferences. It was a lengthy report, but what stood out for me was the finding that only 5% of us prefer promotional offers from brands to show up in social media – even brands we have given permission to contact us. I accompanied the post with the somewhat inflammatory headline – New Research: Americans Hate Social Promotions. This is not factually correct, as the survey did not ask about love vs. hate, but rather about “preference.” I should have been more careful about that.

What I found even more interesting than the research was the negative reaction to it by readers at Convince & Convert, on Twitter, on Google + and elsewhere. While it had several somewhat strident tentacles, the gist of the complaint was “this research cannot be true, because I clearly remember a study saying more than half of all people WANT promotions and offers in social media.” Not a single aggrieved reader cited the research numerically or with a link, but several were convinced that consumers’ desire for special offers and coupons in social media was as insatiable as Ozzie Guillen’s lust to say stupid things.

They remembered the research in general. It stuck with them. But they couldn’t remember the company who published it, what the exact numbers were, or how they were divined. I remembered it too, and looked it up. It was the Lithium and CMO Council study on the Social Brand Experience from December, 2011.

Upon review, however, these reports are not contradictory. If you ask two different questions, you’re likely to get two different answers. Here’s how:

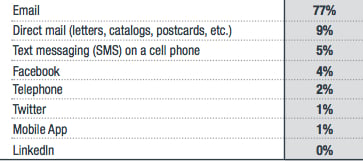

ExactTarget 2012 Channel Preference Survey

Survey Sample: 1,481 Americans, using MarketTools database, randomly sampled and weighted to be representative by age and gender

Response Methodology: Written survey, with permission granted by parents for participation for minors

Question Asked:

“What is your preferred channel for promotional messages from companies whom you have granted permission to send you ongoing information?”

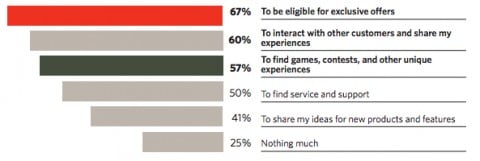

Lithium/CMO Council Social Brand Experience Survey

Survey Sample: 1,300 consumers. Unclear whether they were all Americans, or whether they were existing social media users. Lithium published age and gender demographics, which were not weighted to match national patterns. Uncertain if this was random sample, or self-selected participation

Response Methodology: Online survey

Question Asked:

When I like a brand on Facebook, I expect:

Multiple answers were permissible, and 67% of respondents selected “To be eligible for exclusive offers”.

Well yeah. I’m surprised it wasn’t higher, actually. If I Like a page, I do suspect that they will give me a special offer at some point. That doesn’t mean I prefer those offers to be in social media versus other places.

The Danger of Data

There are at least 4 ways these research reports are different, and consequently why the findings of each are not in conflict.

1. One survey asked about preference. The other asked about expectations

2. One survey allowed for one answer. The other allowed for multiple answers.

3. One survey asked about Facebook in comparison to other channels. The other asked about Facebook “like” outcomes

4. One survey asked about how consumers behave. The other asked about how consumers anticipate brands will behave.

5. There are also significant differences in sample and response methodology.

Given that in the same Lithium results set, 50% of respondents said that they like a brand on Facebook to find service and support, and 41% like a brand on Facebook to share their ideas for new products, do you believe that companies are massively under-executing in the areas of Facebook CRM and crowd-sourcing? Both of those are interesting findings, and just as valid as the “67% of fans want special offers” data point. But the latter was the headline on dozens of blog posts, and maybe we vaguely recall the headline and the Mashable article, and maybe we start to make business decisions based on that piece of information. And then maybe we reject out of hand another data point that we assume is incorrect because it contradicts what we’ve convinced ourselves to be true.

This isn’t about which research is better, or “true”. They are both good studies using different approaches, and there’s no such thing as “true” research, just accurate interpretations of it.